We Don't Know What We Don't Know

In conflicts and state atrocities, what gets recorded versus what remains unseen can differ drastically. Early human rights databases were often plagued by poor quality, inconsistent methods, and patchy records. Activists in the 1980s and 90s labored under challenging conditions, resulting in incomplete data that, once published, was mistakenly presumed objective by officials and the public. Bias of visibility deeply compromised these efforts. A lawyer murdered in front of a courthouse at high noon, everyone will know. If a peasant dies on a dirt road 10 miles from the nearest town, maybe no one ever will.

Dramatic events like car bombings in capital cities dominate headlines, whereas smaller skirmishes away from urban centers go largely ignored. Data is driven by visibility. Thus, what appears in the news or early databases is merely the visible tip of a vast iceberg of violence.

The Myth of Objective Numbers

Human rights investigators such as Patrick Ball, in the late 20th century, employed statistical analysis to navigate the "fog of war," turning fragmented reports into coherent narratives of mass violence. Initial databases were riddled with errors like duplicate entries, misspelled names, and missing dates, but over time, standards improved, and methodologies such as cross-referencing multiple sources became the norm, emphasizing that accurate statistics form the evidentiary backbone of human rights allegations.

While survivors' testimonies provide personal accounts, statistical analyses reveal systematic patterns, such as victims overwhelmingly belonging to a specific ethnic group or region which can expose orchestrated policies behind the violence.

Understanding Multiple Systems Estimation (MSE): MSE employs capture-recapture methodology, where the probability of an event being recorded by multiple sources follows a Poisson distribution. The fundamental equation is:

N = (n₁ × n₂) / m

Where N is the total population estimate, n₁ and n₂ are the number of cases recorded by two different sources, and m is the number of cases recorded by both sources. For multiple sources, we use the Lincoln-Petersen estimator with log-linear models:

log(μ) = α + β₁x₁ + β₂x₂ + ... + βₙxₙ

This allows us to account for source dependencies and interaction effects, providing more accurate estimates of undocumented cases.

Data as a Weapon for Justice

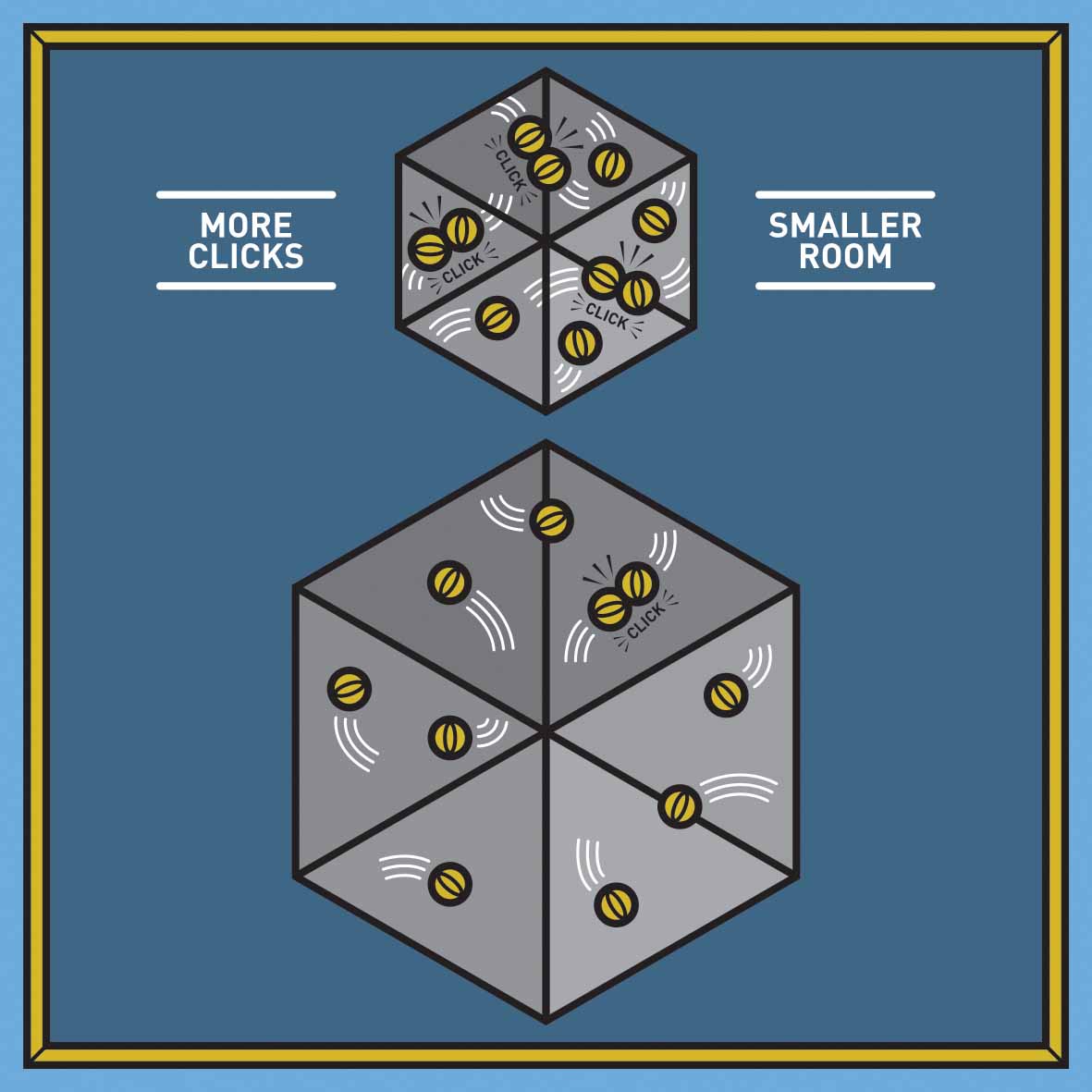

Inferring the scope of unseen atrocities resembles throwing balls into a dark room: the frequency of "hits" gives us information to infer the size of the room. Likewise, documented events can be used as data points to indicate the hidden scale of violence. This statistical approach, known as multiple-systems estimation, evaluates overlapping victim lists from various sources to estimate undocumented killings.

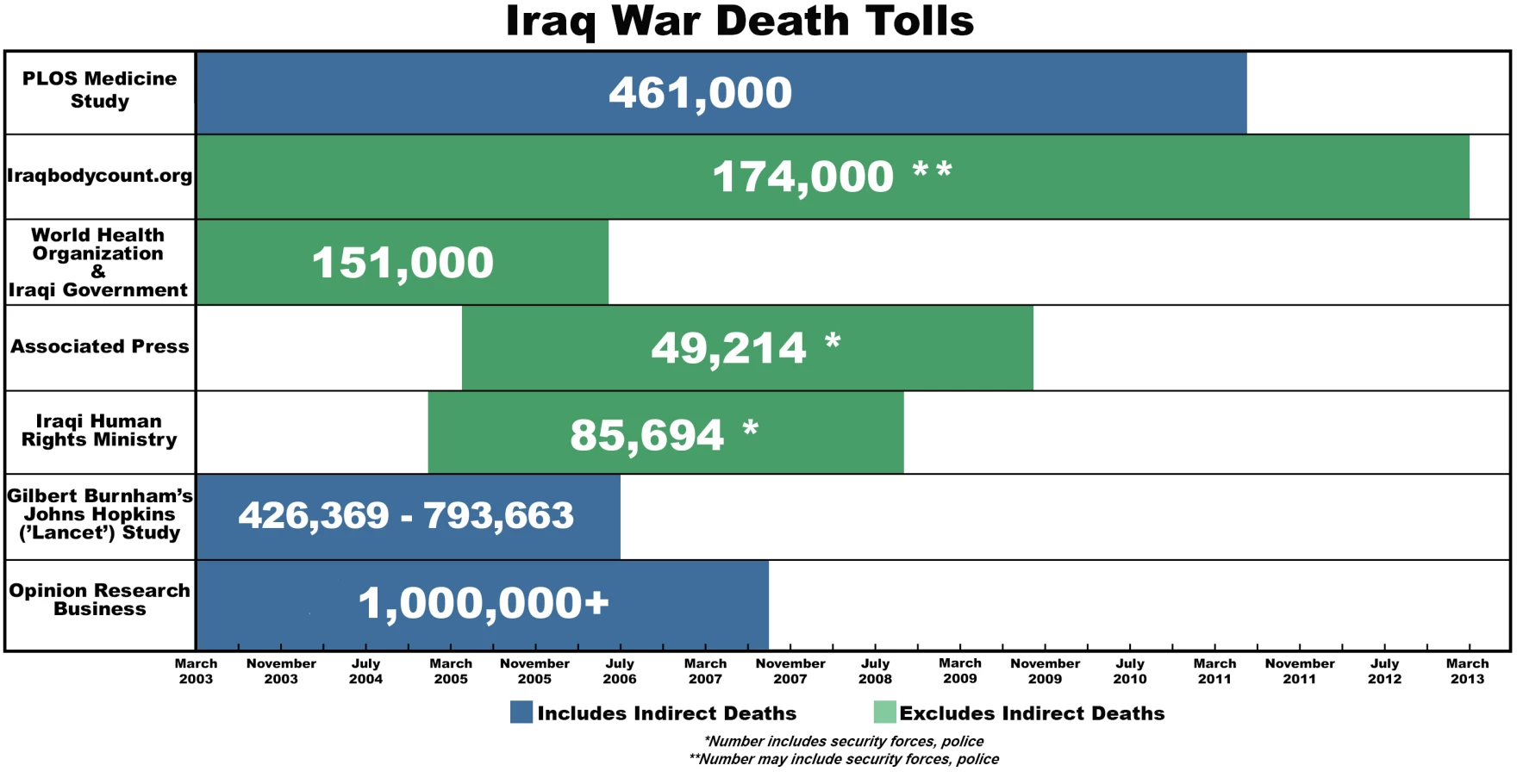

The Iraq War documentation provides a compelling case study in MSE application. The Iraq Body Count project, in collaboration with the Lancet study, employed MSE to analyze data from multiple sources including:

- Media reports (n₁ = 15,000 documented deaths)

- Hospital records (n₂ = 23,000 documented deaths)

- Household surveys (n₃ = 18,000 documented deaths)

Using MSE methodology, researchers estimated that the true death toll was approximately 601,027 (95% CI: 426,369–793,663) between March 2003 and July 2006. This represents a capture rate of only 9.2% by media sources, highlighting the severe underreporting in traditional documentation methods. The MSE analysis revealed that:

- 31% of deaths were documented by at least one source

- Only 2.3% of deaths were captured by all three sources

- The overlap between media and hospital records was 7.8%

This statistical approach demonstrated that relying solely on media reports would have missed approximately 90.8% of conflict-related deaths, emphasizing the critical importance of multiple-source verification in conflict documentation.

Documenting the Iraq War: The challenges of accurately documenting casualties during the Iraq War highlight the limitations of relying solely on media reports. While major incidents received extensive coverage, countless smaller-scale incidents went unreported, creating a significant gap between documented and actual casualties.

Crimes of Policy vs. Individual Crimes

Mass violence fundamentally differs from individual crimes as it arises not from isolated criminal acts but deliberate policy decisions which form organized campaigns of terror, repression, and/or genocide. Individual crimes focus on identifying perpetrators, whereas systematic atrocities require uncovering underlying policy motivations.

Patrick Ball's testimony during Slobodan Milosevic's trial further illustrates this point. Statistics presented showed Kosovar Albanians disproportionately affected by violence, undermining claims of equal suffering and establishing evidence of systematic policy (Ball, 2000). Furthermore, statistical analyses show the systemic nature of crimes of policy. Take for example, that three-fourths of murders occur between acquaintances, with only 25% of those murders occurring between strangers. Notably, if you were murdered by a stranger in the U.S., it is about 1/3 likely that stranger was a police officer (U.S. Department of Justice, 2019).

Ultimately, crimes of policy reveal a systemic and moral crisis.

To kill one person you need a knife;

To kill fifty people you need an assault rifle

To kill thousands - you need a government job

Analysts like Patrick Ball strive for moral accountability by meticulously documenting this "info flow," demonstrating that systemic crimes are far more devastating and morally reprehensible than individual acts of violence. It is through such rigorous data analysis and ethical commitment that truth-seekers confront and reveal the harrowing scale and deliberate nature of mass violence.

The data we collect about human rights violations is not a mirror of objective truth, but rather a reflection of our collection processes and systemic biases. Underreporting disproportionately affects marginalized communities, while fear of retaliation silences countless victims. Crimes are reported unevenly across different regions and populations, creating significant gaps in our understanding. When analyzing human rights violations, researchers must carefully account for these biases and gaps, recognizing that the absence of data does not equate to the absence of violence. This critical awareness of data limitations is essential for developing more accurate and comprehensive approaches to documenting and addressing human rights abuses.

References

- Ball, P. (2000). "Policy or Panic: The Flight of Ethnic Albanians from Kosovo, March–May 1999." American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Ball, P., et al. (2003). "How Many Peruvians Have Died?" American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH). (1999). Guatemala: Memory of Silence.

- Amnesty International. (2017). "Philippines: 'If you are poor, you are killed': Extrajudicial executions in the Philippines' 'war on drugs.'"

- Iraq Body Count (IBC). (2006). "Iraq Body Count Project Methodology."

- Price, M., Gohdes, A., & Ball, P. (2015). "Documents of War: Understanding the Syrian Conflict." Significance, 12(2), 14-19.

- Robertson, G. (2006). Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice. The New Press.

- U.S. Department of Justice. (2019). "Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2019."

- Weidmann, N. B. (2015). "Communication networks and the transnational spread of ethnic conflict." Journal of Peace Research, 52(3), 285-296.