You tap 'Not Interested' on a TikTok video you hate. You feel good. You think you're training the algorithm. You're not. In reality, today's internet isn't primarily optimized for our own good; it's meticulously engineered to lock our attention in place. Platforms thrive not by challenging our views or informing us deeply, but by reaffirming our feelings repeatedly. This is the secret fuel of the modern attention economy: emotional validation disguised as genuine choice.

"The most sophisticated software in existence is tasked with figuring out how to keep you from leaving a website." - Hank Green

The Myth of Choice: How Platforms Control Your Attention

Instagram rarely rolls out new features globally all at once. Instead, updates quietly appear in distant markets like Ghana first, turning entire populations into experimental labs (Newton). Users unknowingly become data points on vast dashboards tracking human attention in real-time. Everything, from scrolling speed and hesitation to micro-interactions, is measured meticulously. You might think you control the content, but each interaction simply sharpens the platform's ability to control you.

Full-screen platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels epitomize this hyper-focused quest for attention. Videos autoplay continuously, deliberately engineered to remove barriers between you and endless scrolling. You swipe, feeling empowered, yet behind every swipe is an algorithm learning exactly what keeps your attention glued to the screen (Fisher and Taub).

Even friendships have become commodities in this digital economy. Snapchat streaks operate bidirectionally, fostering a compulsive reciprocity. Every snap exchanged builds a daily emotional contract, nudging users into constant interaction, regardless of actual depth or sincerity (Lorenz). The goal isn't meaningful conversation, it's consistent, predictable engagement. This engineered reciprocity ensures users return daily, locked into dopamine-driven loops of validation.

"You grant companies access to your attention so that they can alter your choices in exchange for entertainment. You identify with groups and grant them the ability to choose for you which problems you will be most concerned about. One of the most powerful traits of your system is how ardently you believe in your individuality while simultaneously operating almost entirely as a collective." - Hank Green

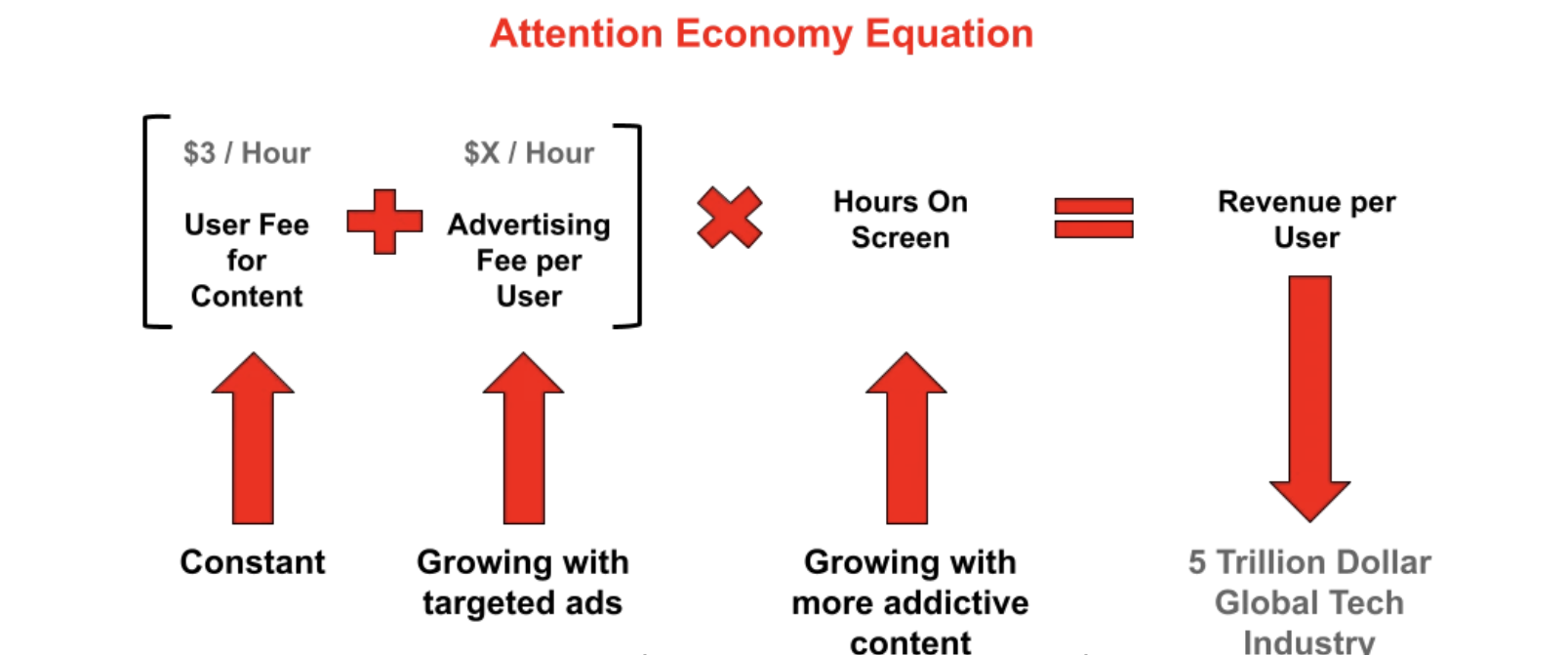

The Attention Economy Formula

The digital ecosystem constantly bombards us with TV, movies, music, podcasts, autoplay, reels, notifications, and endless streams of recommendations. This is not an accident; it's a business model

The value of our attention has remained remarkably stable over decades. Kevin Kelly's analysis reveals that media companies earn an average of just $3 per hour of attention, a figure that has barely fluctuated between 1995 and 2015. This creates a fundamental tension: if users won't pay more, platforms must find other ways to monetize. The solution? Sell the user themselves. Facebook's average advertising revenue per US user reached $53.56 in 2020, while Google's total advertising revenue hit $147 billion. In this equation, we're not the customer, but the product.

"The most important resource of the Information Age isn't information, it's attention... The competition for it is fierce, and the supply is not that plastic. So, you gotta keep finding new places to take it." - Chris Hayes

Echo Chambers and Ideological Bubbles

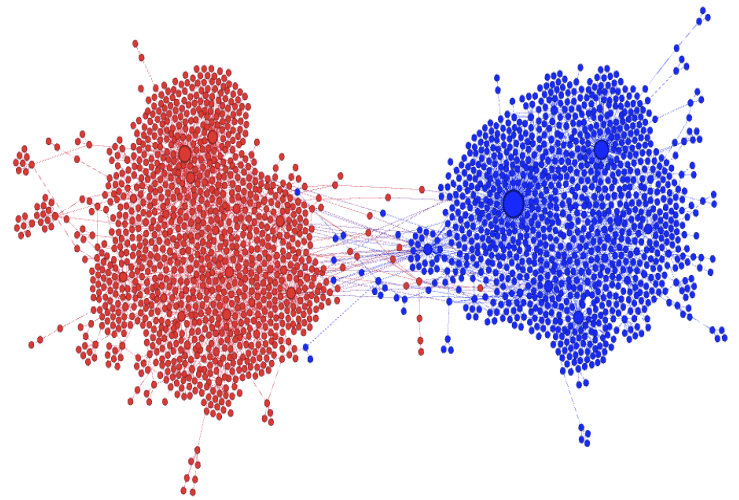

The pandemic starkly illustrated the internet's failure as an educational tool. Despite unlimited access to information, people fragmented into hyper-polarized camps about masks, vaccines, and the very existence of COVID-19. Users didn't seek new insights online; they sought validation for existing beliefs. Rather than educating, the internet validated biases and intensified division (Cinelli et al.).

This polarization isn't unique to health crises. Research analyzing Twitter discussions around India's #beefban controversy revealed stark echo chambers, where users primarily engaged with like-minded individuals, creating distinct clusters of opposing viewpoints. The retweet network analysis showed minimal cross-ideological interaction, demonstrating how social platforms naturally segregate users into ideological bubbles (Cinelli et al.).

Much like the echo chambers of social media, algorithmic complacency thrives on emotional intensity, not nuance. Rage, fear, and controversy are the currencies of engagement. Anger, especially, generates views and likes, not because we enjoy being angry, but because our brains are wired to react strongly to perceived threats, slights, or moral violations. Algorithms, designed to maximize screen time and ad revenue, pick up on this behavioral pattern and amplify it.

Many viewers of a particular content creator may actually dislike the creator or disagree with their message, but the algorithm doesn't care. Neither do advertisers. The system only measures time spent watching, scrolling, and engaging. Attention is attention, ven if it's hate-watching or doom-scrolling.

In such an environment, value and debate are often drowned out by sensationalism. When anger, snark, or performance art generate more clicks than careful reasoning or honest inquiry, the algorithm begins to optimize not for truth, but for tribalism.

Tools That Think For Us

This dynamic leads to a deeper, subtler form of decay: cognitive outsourcing. When you use a tool, you not only gain something, but you may lose something. A calculator helps you avoid manual arithmetic, but overliance on it, especially in youth, can lead to weak mental math skills - even when counting change at the grocery store. Similarly, a child who only ever uses digital clocks may never learn to read an analog one, potentially missing out on a spatial and relational understanding of time.

This isn't just about calculators or clocks. It's about a broader tendency to offload thinking to machines and interfaces, letting them filter what we see, what we remember, even what we believe. In doing so, we surrender not only effort but agency. We don't have to think so much when using these tools, so the result is we don't think at all.

From Print to Pixels: How Media Reshaped Our Minds

Research shows that attention spans are shrinking, but this trend began long before the internet. With each major shift in media, from print to television to the internet, our modes of thinking have been fundamentally reshaped. In Amusing Ourselves to Death, media theorist Neil Postman argued that the decline began with the transition from a print-based culture to a visual one. The "typographic mind," shaped by reading, encouraged focus, rational thought, and linear reasoning. Books require active engagement like following arguments, interpreting abstract concepts, and holding complex ideas in memory.

Television changed that. As Postman noted, the screen favors image over argument, emotion over logic, and entertainment over substance. This shift has only intensified in the age of TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Instagram Reels. Content is now optimized for immediacy, not depth.

You can see this transformation through history. In 1858, the Lincoln-Douglas debates spanned over three hours and were held across multiple towns. Thousands of ordinary Americans gathered and stood attentively through these dense, policy-rich exchanges. These audiences possessed what Postman called the typographic mind, one capable of sustained concentration and logical reasoning, shaped by a culture immersed in books, pamphlets, and newspapers. They could follow extended debates on constitutional law and federal authority because their cognitive habits were formed by longform reading and linear thought.

Now contrast that with the first televised presidential debate in 1960 between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Though Nixon was considered the more experienced and knowledgeable speaker, television gave Kennedy the edge, his calm demeanor, youthful appearance, and polished image won over viewers. Nixon, recovering from illness and refusing stage makeup, appeared pale, sweaty, and anxious. The public's perception shifted not based on the content of what was said, but how each candidate looked on screen. It marked a major cultural turning point: even if Nixon's arguments were solid, Kennedy's image carried the day. From that moment forward, political success depended not just on policy mastery, but on televisual performance.

Today, our political and social discourse often unfolds in memes, facial expressions, and viral clips. Nuance is outpaced by optics. Debates are edited into reels, speeches are clipped into sound bites, and appearance often overshadows substance. The medium has effectively changed how we communicate and reprogrammed what we expect from communication itself.

A Self-Inflicted Sleep

What we're experiencing today isn't just digital distraction. It's algorithmic complacency (term coined by Alec Watson), a self-inflicted sleepwalk through reality, where we passively accept what the machine feeds us.

When the average person spends several hours a day on algorithm-driven platforms, it means their perception of the world is largely determined by what an opaque system decides is most engaging. Not most truthful. Not most useful. Most engaging, in the shallowest sense of the word.

The platforms are not neutral. They reward spectacle over insight. They hide nuance and promote certainty. And they do so at a scale and speed the human brain is not evolved to handle.

We live in a paradox: never before has so much information been so accessible, and yet never before have we been so intellectually disengaged.

The Cost of Convenience

This complacency isn't accidental. It's the price of convenience. Just like the calculator makes math faster, the algorithm makes media easier. You don't have to decide what to read or watch. Hell, you don't even have to scroll, it autoplays.

But what you gain in ease, you lose in discernment.

Much like the person who never learns how to multiply in their head, or the child who can't tell time without a digital clock, we risk losing vital cognitive muscles. Critical thinking. Patience. Curiosity. Skepticism.

These are not innate traits, but are actively cultivated through practice. And when they go unused, they atrophy. Your mind is the prize in a world where every app fights for your attention. The platforms know this. The advertisers know this. Do you?

"A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention." - Herbert Simon

And while attention might seem like a small thing, it's the foundation of everything we value learning... relationships, creativity, democracy. When you lose your ability to pay attention, you don't just become a worse consumer. You become a less free thinker.

Complacency and Mindfulness

In the end, we're complicit. Most of the information the really shows up on our screens and that we consume, is not decided by us, but rather by algorithms designed at knowing us. We know our attention is being hijacked, yet we consent to it anyway. Why? Because it feels good. The internet isn't primarily an information tool anymore, it's a validation machine. People don't log in to become smarter, they log in to feel smarter, affirmed, noticed. Platforms understand this deeply and have perfected the art of packaging validation as an essential emotional need.

Maybe the internet was never intended to set us free. Perhaps its true power lies in exploiting humanity's simples of cravings, and hopefully we wake up to this existential sleep-walk to ultimately lead somewhere meaningful.

"The difference between technology and slavery is that slaves are fully aware that they are not free." - Hank Green

References

Cinelli, Matteo, et al. "The COVID-19 Social Media Infodemic." Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, 2020, doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5.

Fisher, Max, and Amanda Taub. "How TikTok Reads Your Mind." The New York Times, 5 Dec. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/technology/tiktok-algorithm.html.

Lorenz, Taylor. "Snapchat's 'Snapstreaks' Are Becoming a Metric of Friendship." Business Insider, 14 Apr. 2017, www.businessinsider.com/snapchat-streaks-are-becoming-a-metric-of-friendship-2017-4.

Mark, Gloria, et al. "The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress." CHI '08, ACM, 2008, doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072.

Newton, Casey. "Instagram's Global Experimentation." The Verge, 12 Aug. 2021, www.theverge.com/2021/8/12/22621135/instagram-tests-features-globally-first.

Taylor, Chris. "Why People Spend Big Bucks on Twitch Streamers." Mashable, 17 July 2019, mashable.com/article/twitch-donations-why.

Zhong, Raymond. "China Limits Online Videogames, Citing Addiction." The New York Times, 30 Aug. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/08/30/business/media/china-online-games.html.